According to headcasecompany.com, high school football accounts for 47 percent of all reported sports concussions. Because of statistics like this, football programs have been making efforts to reduce head injuries and increase the safety of the game. For three years, the Northwood football program has been involved in a study run by the Matthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center at UNC-Chapel Hill (UNC). The study, called the Behavior Modification (BeMod) Concussion Prevention Study, is concluding this year.

Sports Medicine teacher and head athletic trainer Jackie Harpham first got the team involved.

“I got connected to UNC and their concussion research center because I did my Masters there a few years ago, and my thesis was using the helmet sensors and looking at concussion research,” Harpham said. “So I got connected to them when I was at grad school there, and then when I got this job, they knew we had a football team, and they kind of used it as a way for them to be able to get more research on high school football.”

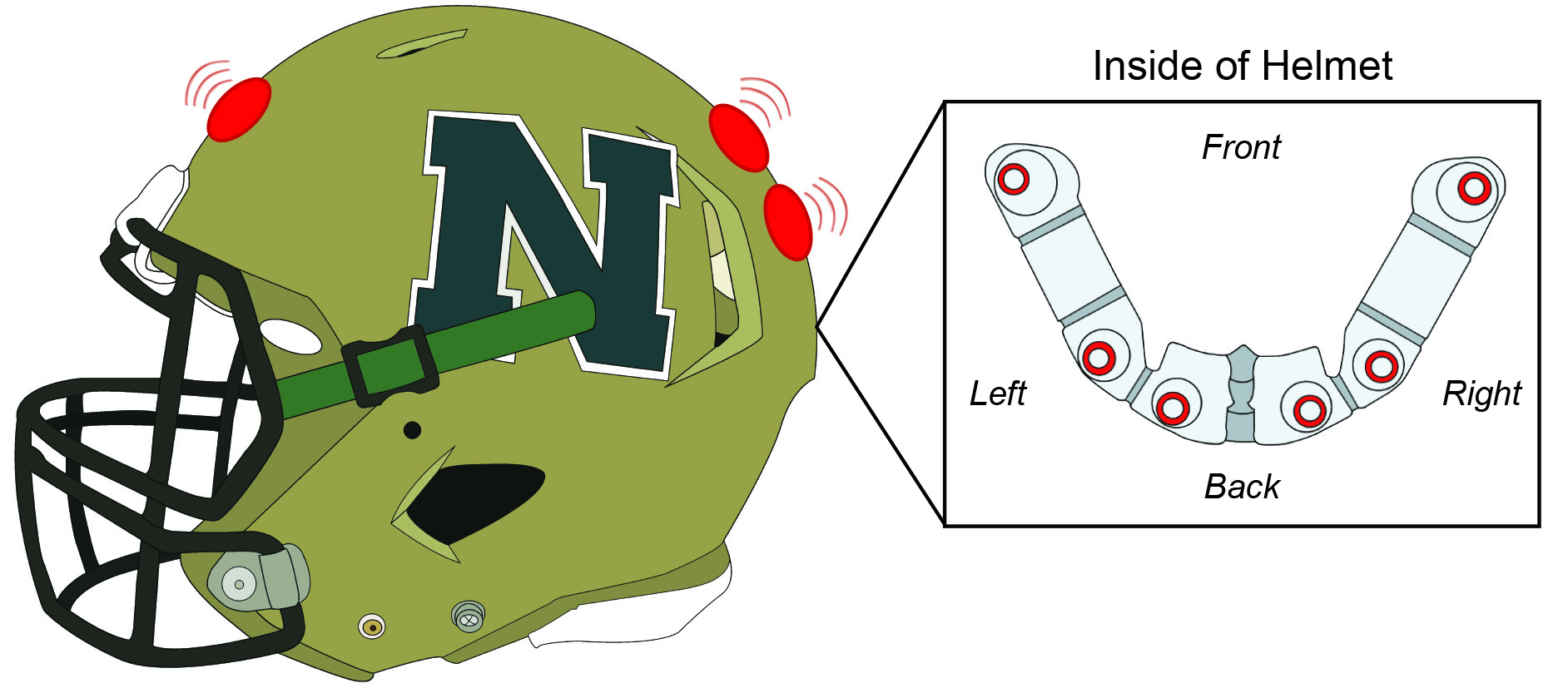

The study is entirely voluntary and centers around the installation of a “head impact telemetry system” (HITS) into the helmets of team members participating. Essentially, the helmets contain sensors that can feed researchers information about the severity of the head impacts sustained. Between JV and varsity, about 30 players have had the sensors installed.

“It just tells us the locations of the head impacts, the severity in a G-force number (the acceleration and force absorbed by the helmet), and then the frequency, so how often they get hit,” Harpham said. “So it doesn’t go, ‘ding ding ding—this person has a concussion.’ It just tells us more about the head impacts they received throughout a practice or a game.”

With this information, players who are identified as high-risk, meaning they tend to receive hits that may lead to concussions, can become part of the BeMod program. Once enrolled in the program, they meet with researcher and mentor Kody Campbell, a student getting his Ph.D. in concussion research at UNC. According to Harpham, Campbell is Northwood’s “liaison to the study.” Campbell spends time matching up film from games and practices to data from the sensors in order to work with high-risk players.

“Kody’s in charge of player technique,” senior Dalton Romagnoli said. “He’ll come and talk to you if your technique is wrong and your sensors are reading high.”

Senior William Yentsch initially chose to participate in the study because “it helps people later on.” He has also worked with Campbell.

“He would just invite us in after school, and he basically would just show us film from previous games and show us how we could improve our technique,” Yentsch said. “He pretty much [teaches you] just to keep your head up to prevent concussions and better blocking techniques.”

Campbell comes from a background in football, and Harpham believes that this helps players identify with him.

“He actually played football in college in Canada,” Harpham said. “He knows football. So I think it really helps because the kids look to him and respect him as a past football player and the fact that now he’s doing all of this research, so I think he’s a really great resource for us to have.”

According to Harpham, Campbell’s sessions have led to a decrease in head injuries for affected players.

“We have seen that the kids who are a part of those sessions have had a positive change, meaning they have less [frequent and high velocity] hits to the tops of their heads after those sessions,” Harpham said. “So we have seen good numbers as far as how those sessions can help.”

Romagnoli believes that the sensors have also been effective because they encourage players to report their head injuries.

“I’d definitely say there’s been an increase in reported concussions because there’s more awareness,” Romagnoli said. “People understand the negative effects of having a concussion, so it’s good in terms of more people reporting concussions.”

Players have chosen to opt out of participation in the study for various reasons, including the fear that information from the sensors will prevent them from playing.

“I think that reservations that our players have about the sensors are similar to reasons why college and professional athletes are hesitant to use them,” Harpham said. “These players are afraid that I might use the data as a way to keep them from playing. Once they listen to me talk about it more, I think they understand that I would never keep someone from playing just because of something the sensor says. It’s only more information we can use to learn more about the hits they may have gotten…. I think at first, they get nervous about anything that might affect their ability to stay on the field.”

Players may also choose not to participate due to the discomfort caused by the installation of the sensors.

“They’re uncomfortable sometimes,” Yentsch said. “The first week you wear them, it hurts pretty bad, but you get used to it.”

However, according to senior Alex Parker, the discomfort is a minor inconvenience.

“I mean, it’s not really like they make a huge difference in the feeling of the helmet or anything, so I was like, you know, might as well let them have a little bit of extra information to help out their research,” Parker said. “I really just don’t see any downside to it.”

– By Sara Heilman