Hey there! My name is Ella Sullivan, and I’m the Co-Editor in Chief for The Northwood Omniscient. In this podcast, we’ll be covering the findings of Duke researcher’s study on PFAS in Pittsboro waters. An earlier version of this story was covered as “Something in the Water” in one of our 2019-2020 print issues.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, more commonly known as PFAS, have been in the Haw River since at least 2017. According to the Environmental Protection Agency or EPA, PFAS are synthetic chemicals that have been used in food packaging and household products since the 1940s. PFAS were originally found in the Haw River when Heather Stapleton, a researcher at Duke University, was testing Robeson County waters for PFAS in 2017.

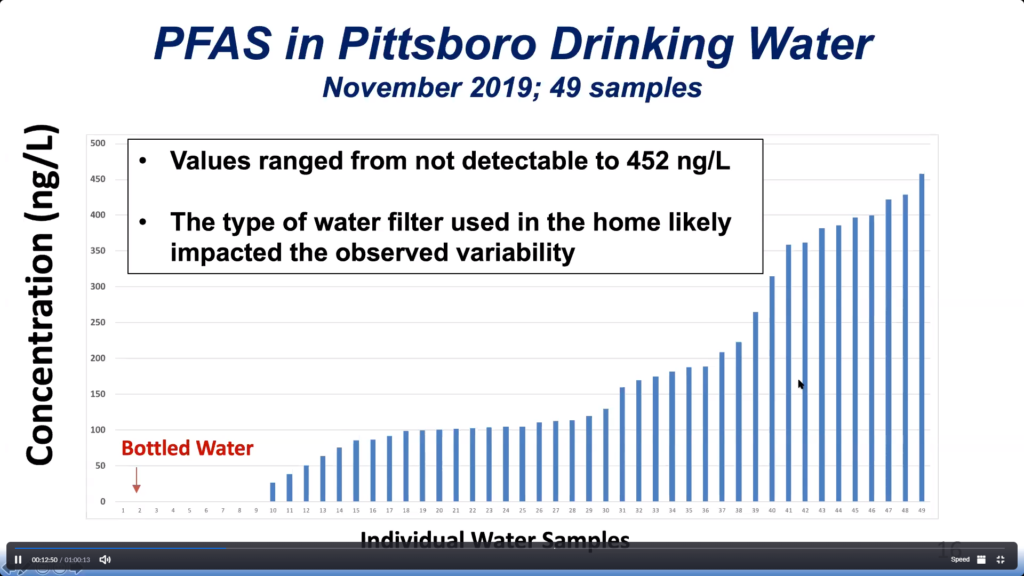

In order to research PFAS in Pittsboro, Stapelton further tested 49 Pittsboro residents’ blood samples and compared them to water samples in order to find a correlation between the two. The purpose of the study was to determine if levels of PFAS in Pittsboro residents is higher than the general population of the United States.

On Oct. 24, the findings of Stapleton’s study were released on a zoom town hall on Pittsboro and Haw River PFAS.

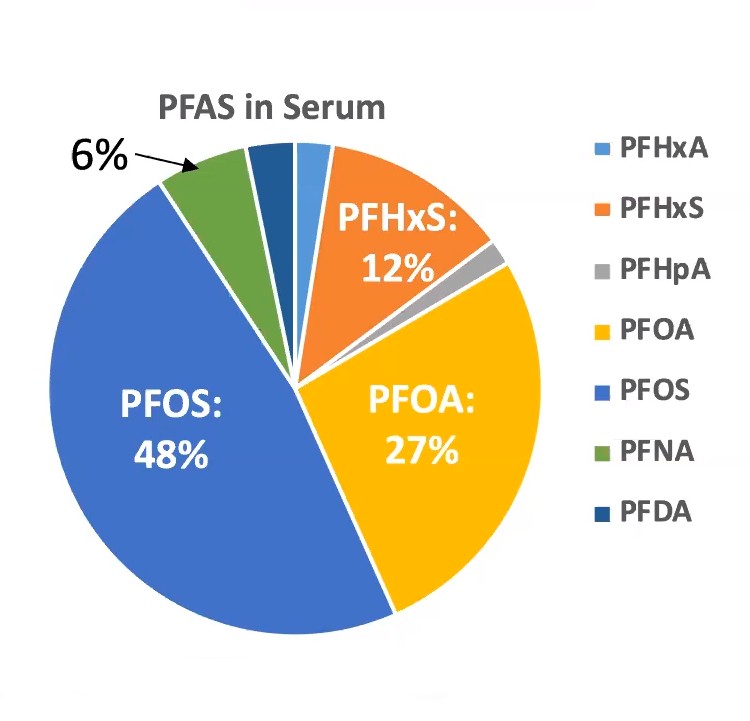

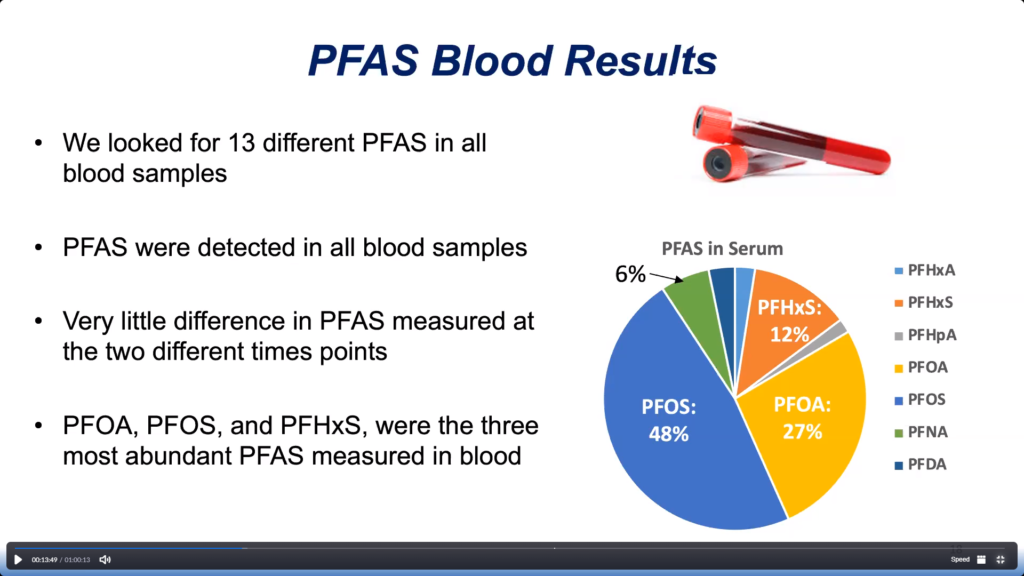

The most common forms of PFAS found in Pittsboro residents’ blood are commonly referred to as PFOS and PFOA. Values found in tested water samples ranged from not detectable to 452 nanograms per liter.

Blood samples from the study were tested for 13 different types of PFAS on two dates. PFAS were detected in all 49 blood samples. Between the two sample dates, very little difference in PFAS levels were noted but levels both times showed high concentrations of PFAS.

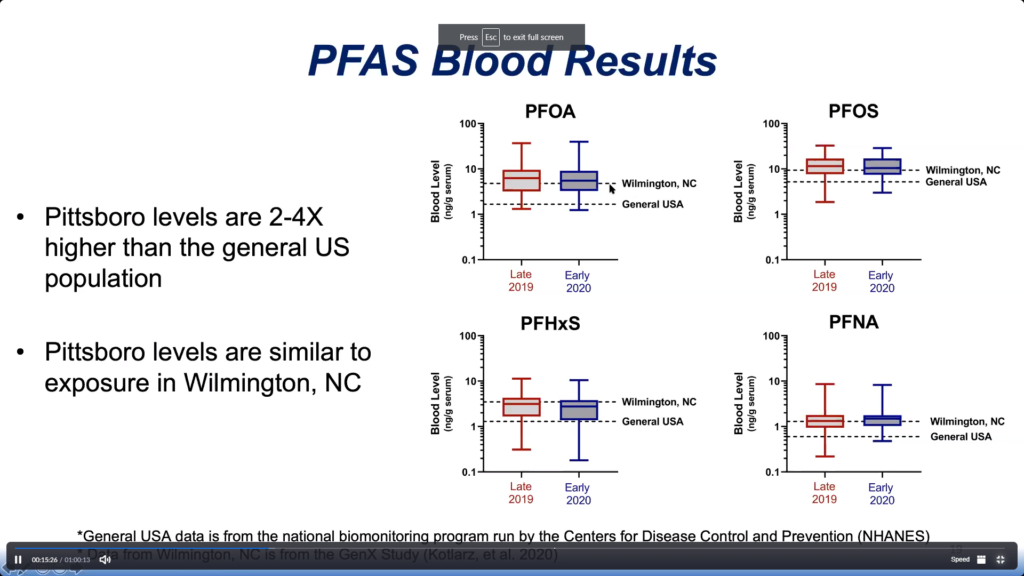

“So you can see through all these PFAS, PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS and PFNA, the concentrations in the serum of Pittsboro residents was two to four times higher than what we see in the general U.S. population.”

That’s Stapleton discussing her findings during the Oct. 24 town hall.

Duke researchers also believe that drinking water is the primary source of exposure for PFAS in Pittsboro. The EPA has established a non-enforceable health advisory for PFOA and PFOS in drinking water of 70 nanograms per liter. The maximum level of PFOA in Pittsboro is 48. However, many states have made moves to create maximum contaminant levels such as New Jersey creating a threshold of 14 and Michigan creating a threshold of 8. Other states have moved to regulate the sum of all types of PFAS. States like Vermont and Massachusetts have limited this threshold at 20. The maximum sum in Pittsboro drinking water is 225. Pittsboro’s sum is over 10 times the level established in Vermont and Massachusetts.

Stapleton’s study cannot say anything about the health risks at this time as a larger scale study is needed. However, The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry or the ATSDR claims that certain PFAS chemicals may lead to changes in infant and child development, the body’s natural hormones and the immune system. The ATSDR also claims exposure to PFAS may lead to higher cholesterol levels, increased cancer risks and lowered pregnancy chances.

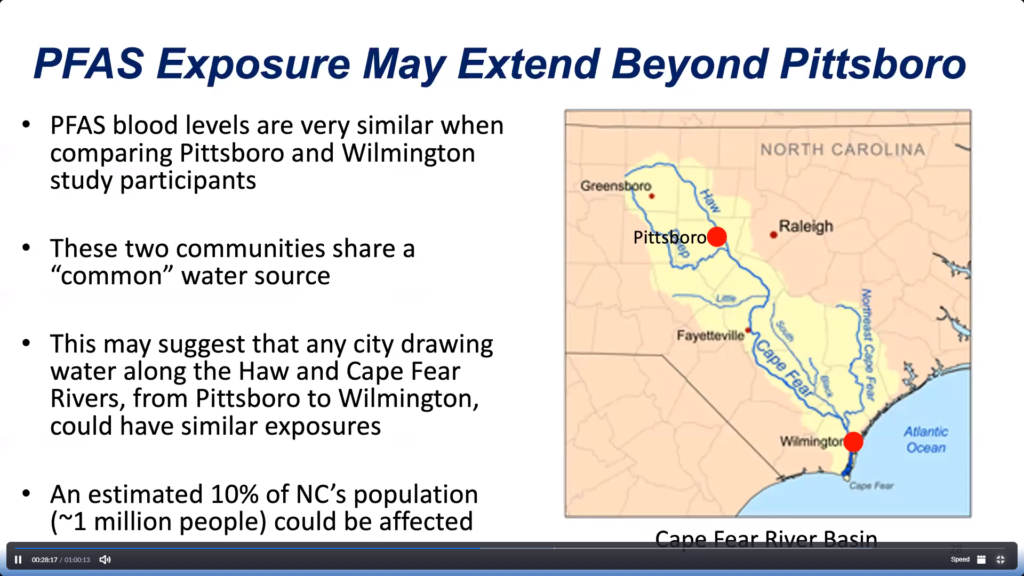

“So I showed you previously that the serum levels or blood levels of PFAS in Pittsboro were similar to what has been observed in Wilmington. I think most people are under the assumption that these levels measured in Wilmington are coming from the Chemours facility that was releasing GenX and other PFAS into the Cape Fear River. So for exposure to GenX and other ither based PFAS like natheum byproduct 2, that is true. That is coming from the Chemours facility. But if we are talking about the legacy PFAS, particularly PFOA and PFOS, those sources are likely upstream, and it seems likely that those sources are the Haw River that empties into the Cape Fear. So as PFAS are being transported down through this watershed to Cape Fear or they are entering the drinking water source for the city of Wilmington, the source of their water is the same which is likely why these patterns are so similar. This also suggests that any communities pulling drinking water between Pittsboro and Wilmington, particularly from the Cape Fear River, are likely to have similar exposures. And if we think about the number of people that includes these different utilities pulling water, that’s as many as one million people or 10% of our state’s population. So this really desires more attention at the state level to understand the full implications of exposure for the North Carolina population and what the health risks really are.”

This further research will be continued by Jane Hoppin, a NC State University researcher. Hoppin’s group has worked previously in Fayetteville and Wilmington to investigate exposure to PFAS. Funds for that study have been expanded to include Pittsboro.

Stapelton’s group has many suggestions on how to reduce exposure to PFAS including installing water filters, avoiding stain repellent treatments and encouraging restaurants to use fluoride-free food packaging.

To learn more about Stapleton’s findings visit sites.nicholas.duke.edu/stapletonlab/.

Thanks for listening to this podcast on behalf of The Northwood Omniscient, we hope you learned something from it! If you enjoyed, be on the lookout for more podcasts like this to come in the future!

Slides from Stapleton’s town hall. To watch Stapleton’s town hall in full, click here.